You are traffic: pattern-finding, chaos, and conspiracies

SPIEGEL: Professor Adorno, two weeks ago, the world seemed in order…

ADORNO: Not to me.— ‘A Conversation with Theodor W. Adorno’ Der Spiegel, 1969

Monatshefte, Vol. 94, No. 1, Rereading Adorno (Spring, 2002):14

Was the coronavirus created in a Chinese lab? Is it a left-wing conspiracy to crash Trump’s bullish economy? Is a shady cabal of powerful elite pulling the strings and ruling the world? Is Trump unconcerned by American interests because he’s controlled by the urinary-kink kompromat of Vladimir Putin? Is power—and strategies to maintain power—encoded into the systems which sustain the world? And is that all the fault of the Jews/the Chinese/the Muslim/the Russians [delete as appropriate]?

One of these claims is not like the others… but perhaps the superficial similarity, and the role the bogus agentive conspiratorial claims therefore play in discrediting the structural, is the first step in understanding their persistence, their usefulness to the status quo.

In times which are routinely described as unprecedented, uncertain, and troubling, a familiar trouble and all-too-precedented strategy for certainty is widespread. Conspiracy theories, conspiratorial thinking, and accusations of such are foaming and proliferating, but they do so asymmetrically and tellingly. Like all stories, all products of culture, conspiracy theories are downstream of material reality and while they are fictional, they reveal truths about our social and material relations. And like so much else, the chaos of the current crisis show up relations which have long-since shaped our world in sharp relief.

To begin, let’s examine the role of conspiracy theories in our disordered ‘ordinary time’. If stories are a ‘strategy against a madness in which we are overwhelmed and overcome’ by the chaos and plurality of living, then nowhere is this central function of narrative more visible or tragic than as the motor of conspiracy theories. They are widely ridiculed—and often ridiculous—but conspiracy theories motivated Timothy McVeigh to carry out the Oklahoma bombing and David Copeland to set off nail bombs in east London’s Brick Lane and in Soho. The power of such a story can be phenomenally destructive and its consequences unspeakably grik. McVeigh and Copeland both shared a version of the same wicked and tragic story. They believed they were striking out against a shadowy, global elite—at root a Jewish cabal—of bankers, politicians and media Moguls - ‘the secret rulers of the world’. It is an updated version of the story that Hitler told in Mien Kampf, which in turn borrowed and adapted from hundreds of years of institutional Christian anti-Semitism. But in all these stories the ‘monstrous Jew’ is only ever a proxy: the bogeymen of conspiracy theories have worn essentialising Semitic clothes, but the object of fear has always been a force (mis)understood as both insidious and totalitarian: power itself.

In his gonzo journalistic book, Them, Jon Ronson investigates a variety of extremists - US neo-Nazis, British Jihadis, Ulster Presbyterians and Ku Klux Klansmen - and finds that they all share versions of a common story: that some global cabal exists who control everything. Some versions envisage an Orwellian ‘New World Order’ - Big Brother updated for the internet age. David Icke is a paranoid former sports presenter who has dedicated the last twenty-five years telling anyone who will listen that the powerful elite are in fact a disguised race of twelve-foot baby-eating space lizards keeping the world in bondage. Ronson describes a farcical but all too real dialogue with the American Anti-Defamation League, an organisation whose admiral aim is “to stop the defamation of the Jewish people”. They see their role as documenting and publicly condemning incidences of anti Semitism in order to prevent the normalising of anti Semitic discourse in the manner that enabled and propelled the rise of Hitler. They have condemned Icke’s conspiracy theories as anti-Semitic. They recognise the tropes - sub-human, baby eating, blood drinking - these are all lifted directly from mediaeval anti-Jewish stories like the ‘Blood Libel’. This was the hateful story that observant Jews required the blood of children to make matzah bread. It is a story that launched a thousand pogroms. ‘Lizard’, the ADL reason, is code for ‘Jew’. Ronson, himself Jewish, spent extensive time shadowing and interviewing Icke and was much less certain. However clumsily they were delivered, Ronson believed Icke’s claims of respect for Jews and Judaism. Ronson was increasingly clear that lizard really did mean lizard. ‘That’s code for Jew, too.’ he was flatly told.

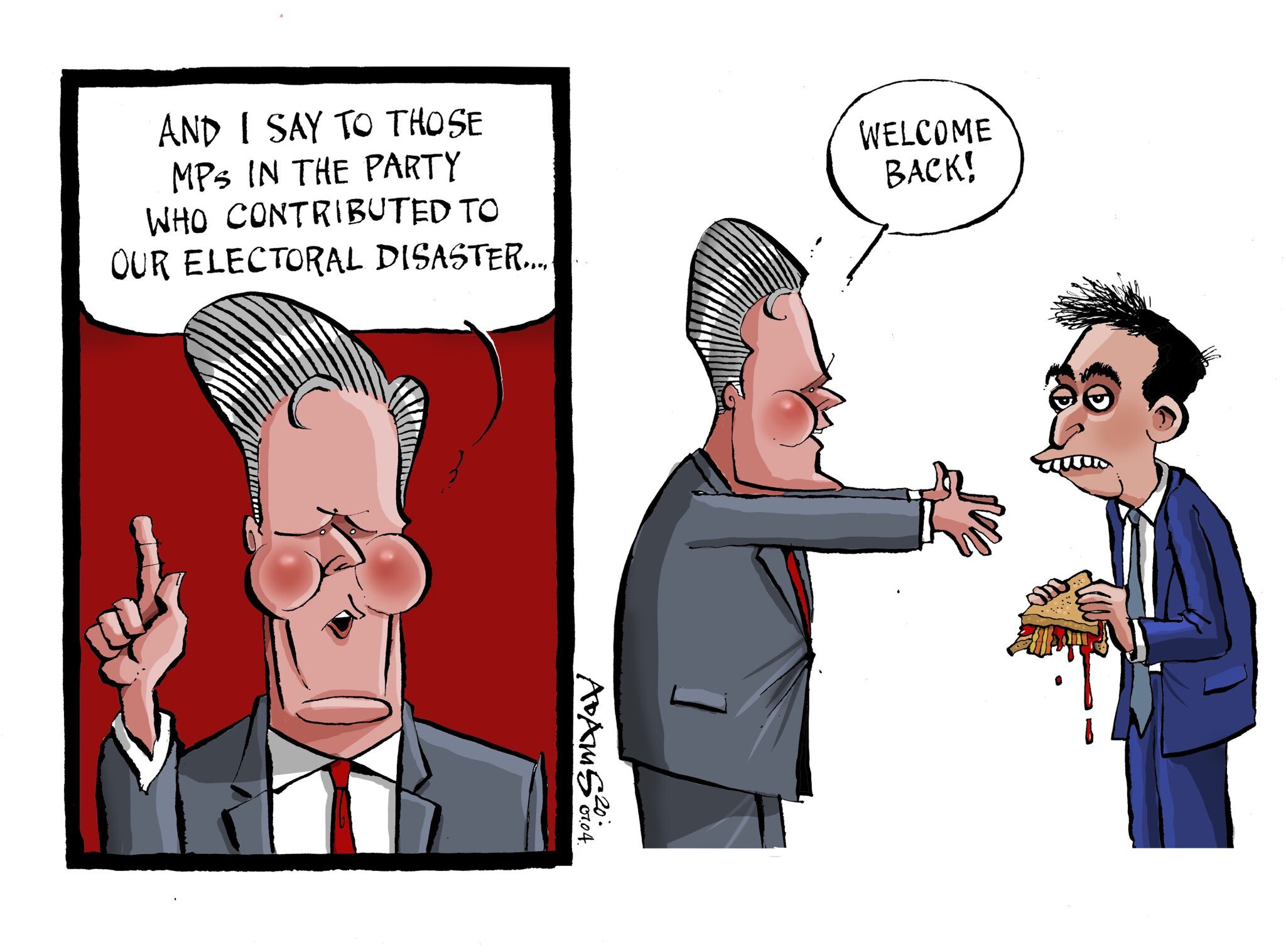

There is a fuzzy mind-fuckery at work in reading Ronson’s comic account of this conversation. Rather than as a piece of Dadaist theatre, it is possible to use narrative approaches in order to understand why Icke and the ADL are so fundamentally unable to understand each other. Language itself can and does encompass broad stories and so, for example, the trope of the greasy money-grabbing conniving lawyer is often conscious or unconscious code for shadowy Jewry. It was hard to know whether it was sly and knowing, or just alarmingly unaware, when many of the commentators on the British Labour Party’s 2010 leadership contest, observed in their newspaper biographies of the winner Ed Miliband that his background was ‘intellectual’ ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘north London’, all of which were dog-whistle pitch-perfect cries of anxiety that for the first time since Disraeli, a Jew might be in the running to be Prime Minister. After two parliaments marked by panic about antisemitism within the Labour Party, Miliband’s return to the front bench after Starmer became Labour leader a few weeks ago was marked by a cartoon in which Miliband was depicted as hook-nosed, eating his infamous (non-kosher) bacon sandwich depicted dripping with a ‘ketchup’ which only weeks before would have conjured that historic ‘blood libel’ were it only still in the interests of Labour’s opponents. The conspiracy theory and identity politics meld mutably in response to power. Once again, storytelling’s meaning—all conspiratorial thinking, all resistance to it only exists in storytelling, not material reality—slips, slides and preserves power, unmoored outside the web of narrative. While crass, the ease with which neo-Nazi versions of the conspiracy story slip between ‘Hollywood liberal’, ‘financier’, ‘communist’ and ‘Jew’ confirms that the ADL are not themselves just finding an abstract pattern within language, but are recognising familiar patterns of discourse which are real, dangerous and corrosive.

Christian Adams’ cartoon in London’s Evening Standard, from 7 April 2020—as shared on twitter by the paper’s editor, architect of a decade of austerity while Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osbourne.

That Icke has employed plotlines with a bloody history into his tragic fantasy of a global conspiracy does not, in itself, make him an anti-Semite, only a good-natured fool. For hundreds of years, the culture that produced David Icke told some of its most terrifying stories of monsters - Christ-killers, child-abusers, bloodthirsty usurers and merciless terrorists - about Jews. It is unsurprising that when Icke invents a monster, the language and imagery available to him is recognisable from the story of anti-Semitism. No intentional anti-Semitism is required to produce this effect—simply discourse and generations of storytelling. Though he borrows from a grim history of anti-Semitism with an excruciating ease, sometimes, in Freud’s apocryphal pronouncement, a cigar is just a cigar, and so a lizard really is just a lizard. This is the slippery nature of discourse: when we describe a pattern that we find in the chaos of reality, we have no option but to use language that has been used to tell other stories before this one. With that language, come the vestiges of those stories: contradictory, offensive, absurd or helpful though they may be.

There is a double layer of confusion: we can grasp for patterns that are created not by ‘reality’ but by the stories we tell. We tell those stories in the multi-layered associative storytelling language that has come before us. There is no neutral way to speak, there is no clean language. Further complicated, this is an uneasy process, because becoming aware of how misguided our pattern-finding instincts can be, does not mean that there are no patterns out there. Reflection is necessary to guard against getting caught up within erroneous pattern finding within useful larger pattern finding, as seems to have been true in the Anti Defamation League’s assessment of Icke. We have to forgo the aim of achieving ‘the truth’, ‘the one true pattern’ which accounts for all the other patterns. Reality is always incorrigibly plural.

Many of Ronson’s travels with the pattern-finding extremists centre on a truly existing meeting of the leaders of politics, business and media in the Bilderberg Group. Depending on who you ask, the Bilderberg Group is either an open off-the-record forum for powerful people to speak freely and broker peace and prosperity, or is the headquarters of the lizard people and the focus of their ambiguously Semitic plot. Whatever the ‘reality’, Ronson’s account of meeting real members of the group finds people who are neurotic and machismo-addicted, immature and chaotic. More pathetic than sinister. It is largely only since the publication of Them that Bilderberg meetings have received any real media comment or notice, and the secrecy of their meetings is largely kept by the attendees. Ronson managed to speak to several members on the basis of anonymity. He learned that real-life Bilderbergers enthusiastically share accounts of the latest conspiracy theory about them - in much the way that politicians seem to prize the framed originals of their most grotesque newspaper caricatures.

Ronson asked one insider why he thought conspiracy theories themselves were so abidingly popular. The answer describes a poignant collective response to the barely organised chaos of global capitalism. We now live in the period after the traumatic fragmenting of trust in the twin power structures of state and religion. In the internet age, this generation experiences more high-speed chaos as material from which to divine sometimes outlandish patterns.

‘Let’s face it,’ my deep throat had said to me, ‘nobody rules the world any more. The markets rule the world. Maybe that’s why your conspiracy theorists make up all those crazy things. Because the truth is so much more frightening. Nobody rules the world. Nobody controls anything.’

‘Maybe,’ I said, ‘that’s why you Bilderbergers love to hear the conspiracy theories. So you can pretend to yourselves that you do still rule the world.’

‘Maybe so,’ he said.

This claim that ‘the markets rule the world’ has significant implications for our pattern-finding minds. This is a claim that implicates both everyone and no one. Worldwide, no one and no group has the ability to either absent themselves from capitalism, nor to control or drive it. That there are ‘winners’ within this system’s own terms, does not presuppose a controlling intelligence by or on their behalf. There is no secret room in which Messrs. Moneybags are chosen and ordained. But it is true that through combinations of contingency, inheritance and chaos, people who become powerful do end up in the same rooms as each other. To read into the existence of the Bilderberg Group a conspiracy is a fatal pattern-finding mistake. Beyond a desire to avoid this, it is essential to critically interrogate the desirability of ending up in such rooms and not to accept the story that such rooms are what success looks like. The chaotically indifferent nature, and species-wide structure, of contemporary capitalism makes this historical moment particularly susceptible to pattern-finding, solipsistic delusions.

These become further enmeshed in the current crop of Coronavirus conspiracies. The dynamics remain the same, warding off the horror of chaotic reality, always incorrigibly plural in its causes, and nature piteously indifferent, defiantly material and anti-narrative. The key characters can take on complementary (if not also implicitly self-contradictory) garb: the ‘wrong kind of capitalists’, warping its pure forms with its greedy acceleration, somehow in sync with that old foe, The Reds - this time with ‘slitty eyes’, rather than with big beards and bottles of vodka. Once again, we can take flight from the pressing twin concerns of an earnest and dispassionate reckoning with the chaotic, untamable and ambiguous horror of reality and deciding in the face of such complex indifference, what is to be done.

Culture, and the stories which make it up, is downstream of material reality, we leftists have always claimed. Identifying a conspiracy, or conspiratorial thinking, has little explanatory power on its own. Unmoored from materialsm, loosed in a morass of discourse, conspiracy-theory spotting alone, has become a method of policing class and policing the inchoate narratives of class politics which aim to simultaneously strike out at growing inequality while leaving those markets which rule the world unchallenged. The bizarre phenomenon of ‘QAnon’ is a baroque and loosely defined network of conspiracy theories encompassing a US deep-state, the crimes of Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama (see Trump’s contentless new conspiracy theory ‘Obamagate’ of recent days as only a more recent part of this wider drama) and other figures of the liberal elite, paedophile-panics both real and imagined, ranging from so-called ‘Pizza-gate’ to the trafficking networks of Jeffrey Epstein, and the sense that the purity of the American dream has been corrupted and stolen. Bizarre, incoherent, generationally specific (technologically, QAnon has spread through ‘boomer’ facebook while it remains relatively marginal on platforms where the mean age is younger and wealth higher) this conspiratorial thinking has become a hallmark of the discursive character of ‘the redneck’ whose latest iteration in ‘the MAGA chud’: stupid, racist, small-minded, white, illiberal and intolerant—cousin to the Brexit-voting ‘gammon’ across the Atlantic. QAnon conspiracists have long seized on the rollout of 5G technology as a danger, just as they have concerned themselves with ‘chemtrails’ in the air, flouride in the water-supply, magnetic fields, and other intangible agents of chaos inflicted on them by the powerful, all the more insidious for their invisibility and inevitability. That a real invisible and somewhat indiscriminate danger should arrive at the same moment, allowed a fateful spurious correlation to emerge and a generation’s worth of material antagonism to be joined to an unrelated phenomenon in a haphazard world.

Two counters are necessary to this view. First, the misapplied sense from the ‘MAGA-chuds’ that their government has not been working for them has a sound and unarguable material basis: that they now distrust government’s ability to keep them safe in a pandemic, must surely be related to the fact that government has so grievously failed their communities and class for generations. Secondly, and relatedly, if conspiratorial thinking were the hallmark of ‘red-necks’ alone, then it is necessary to ask how the most productively dumb conspiracy theory of recent years has been the wild panic in coastal America about the role of Russian interference in US politics, which culminated, not with a bang but a whimper, in the failed impeachment of the 45th President just weeks before coronavirus swamped the US republic.

The one data-set necessary for interpreting current US political trends: Brookings Institute data on the change in the decade since Barack Obama’s election of wealth within households and congressional seats, divided by election outcomes and party registration.

Capitalism is no longer working—was it ever?—for the communities represented by parties wholeheartedly engaged in unapologetically in its promotion. Stories are now required—or rather, were always required—to prop up that illusion. Identity narratives have been the cover by which the contraction illustrated in the graph above have taken place: an illusion that racial, gender, and other diversity indicators can be evened out to provide fairness within each strata of the material distribution of wealth—equality in an unchanged world—thereby legitimising the very uneven distribution of wealth that motors the resentments of racism and every other identity -ism in the first place. This is why weaponised claims of antisemitism could be so effective against the modest social democracy of Corbyn’s Labour party, but why the out-and-out tropes of the Evening Standard cartoon were met with indifference from the same quarters who were previously so vocally outraged. For capital, nothing is now at stake in pondering which brand of managerialism—blue flavour or red flavour—markets operate under. In the ‘land of the free’ it is essential to find the stories about freedom to be unreliably rigged, lest your attention to turn to the story of freedom itself as the source of your troubles—hence America’s status as the nation of the conspiracy theory par excellence.

Conspiracy theories operate like detective stories. We have found a breach in the established order, they claim, the badness can be identified, exposed, removed. Ultimately their claim is that the world seems ‘in order’—or was in a recent past that can be returned to, could be if only the specific badness were removed. Beneath the panic of corona-conspiracies is something of a slave morality presented in almost touching naivety: the world could not be as chaotic, as quixotic, as piteously indifferent as to throw up a novel virus capable of killing us… surely? A few weeks ago the world seemed in order, they appear to claim. With Adorno we wish to respond, ‘Not to us…’

And here’s the kicker—and the subtlety that’s required at the moment: conspiratorial thinking plays a key obscuring role, pointing in two confused directions. Not only does it respond to the necessary existential chaos of any possible world in which a deadly virus was likely, even certain, from century to century, including the ‘strange new worlds’ we unreliable narrators so ardently want, with which we need to respond with ambiguity. Further, conspiratorial thinking obscures how power actually operates, in this actual world, in the social relations of capitalism and our relations to the means of production. Removing an identity group—imagined (lizards) or really-existing-but-not-to-blame (jews)—or ‘recententering’ another simply produces totalitarian horror or woke capital, whose torture-centres may be run by women, or petrochemical companies headed by gay men, but a world of torture and rapacious capital nonetheless. The base of the right wing of the capitalist class engages in the former conspiratorial thinking, the left wing of capital in the latter deckchair re-arranging. Both simultaneously accuse those materialists who seek to remake the world of thinking conspiratorially: because to confront the power of the structure of capitalism, if we are accustomed to thinking agentively (that the ‘badness’ happens at the level of the motivated will of ‘bad actors’) rather than structurally (that it is not the bad apples that spoil the barrel, but the bad barrel that spoils the apples) this appears to be the same genre of claim. A materialist, antinarrative analysis helps us pick these apart and serves as a balwark against storying ourselves into the corners of coronavirus conspiracy, identity politics and its discontents, or narratives which legitimise the established order of capital beneath a cry of ‘Russian interference!’ or ‘Brexit racists!’

Stories have a tendency to be told on the assumption that the speaker is the main protagonist. Pattern-finding conspiracy theories set out to explain how we live now such a perspective. A decade ago, sat nav manufacturers TomTom placed billboard adverts aimed at frustrated car drivers by the sides of busy roads. They read, in gnomic block capitals, ‘YOU ARE NOT STUCK IN TRAFFIC. YOU ARE TRAFFIC.’

Conspiracy theories display the same confusion of perspective that the advert parodied. It is deeply alarming to recognise that we are participating, inevitably and uncontrollably, in a financial system, which, like ‘traffic’, we can attempt to influence but no one - not a government, nor revolutionary political party, nor a cabal of flesh-eating lizards - can control. Both traffic and capitalism exist only in our relations and relationships. It is much easier to imagine ourselves outside of a sinister system marshalled against us—and conceive of ourselves as pure, honest, rational actors, caged within confines from which we could only be released if we felt or thought ourselves more purely into a position of clarity beyond its bounds.

Whether there is a deadly virus stalking the planet or not, whether we wish to rescue capitalism from its neoliberal cronyism and recreate a mythical ‘pure’ version of it, or overcome it and build a strange new communistic world, one reality becomes clear that requires no conspiracy to be cracked, no shadowy cabal to be unmasked, no secret to be told: we are not stuck in capitalism. We are capitalism.

Now, the old question remains but the decks are somewhat clearer: what is to be done?